Thursday, February 12, 2009

Wednesday, February 11, 2009

Linda: Khajaraho, Feb. 9-12

Khajaraho, Feb. 9-12

From one perfection to the next, truly, this country is a wonder of art, of poetry, of genius. We left the wonders of the Mughal world to go backwards again in time. This time, we traveled (uncomfortably) on an amazingly crowded local bus – crowded both inside and on top! Fortunately, we had seats, so by dint of elbow and knee, I could maintain my personal space from encroachment on those who had to stand for the entire 5+ hour journey. It really wasn’t too bad as one’s need for “comfort” lessens with time, which I think is a good thing. I was delighted that our lovely hotel in Khajaraho had a splendid, working, plentiful shower in which I could refresh myself from the experience!

Khajaraho is a city of temples, built at the height of medieval India from 900-1100 AD. It is a city founded both in legend and in history. In legend, it was said that a beautiful maiden was bathing in a lake at night. The moon god, struck by her loveliness, came to earth; the offspring of their love destined to be a great king who would found a kingdom and religious center. In history, it is the seat of the great Chandala kings, kings who, through their might and integrity, maintained their kingdom at this pivotal crossroads against waves of Islamic invasions and who, through their immensity of character and patronage, built these temples of exquisite perfection. Here, we see the culmination and perfection of all that had gone before it. Originally, there were over 85 temples in this area – each a jewel, and each dedicated to some aspect of the divine. Now, 25 temples remain, the most inspiring are 10 set close together. When they were built, these temples surrounded a lake – one can only imagine the splendor of their outlines reflected in the still water.

The glory of these temples is two fold – first of all in the incredible geometry of each temple, an overall geometry, where the spires of a temple increase to the lofty heights of the tall, conical spire that covers the sacred center, a spire reminiscent in design to the lofty mountains of the Himalaya, the abode of the gods. The geometry of the building is then accentuated by the carvings on the outside. From a distance, besides the play of the spires, one against the other, one also notices the interplay of lines, both horizontal and vertical, bands of sculpture that lead the eye around and upward, but predominantly and irresistibly upward toward the liberation of the sky.

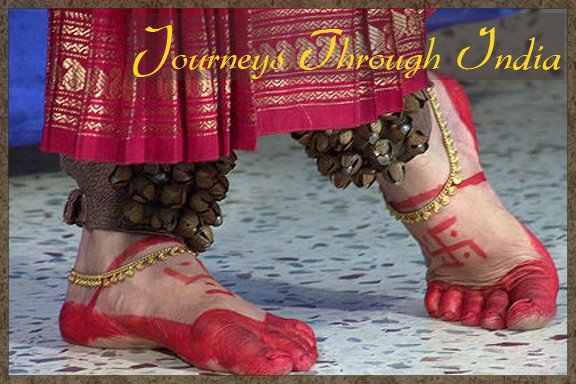

Then, as one approaches more closely to the temple, the magnificence of the whole focuses onto the domain of the individual sculptures that surround the temples, row upon row, going both around the temple and upward. Each temple stands on a pedestal. The sculptures, about a foot high on average, on many of the pedestals show everyday life: harvesting, warfare, couples, hunting, a sculptor. The details, even after a thousand years, are astounding. The faces, natural but not naturalistic. Then, as one ascends the steps to the temple proper, one looks at the sculptures surrounding the outside of the temple. Here, the sculptures, often three feet high, are of a more lofty subject, from regal and aristocratic on the bottom tier to the realm of gods as one looks up. Again, the depictions are very detailed, natural but not naturalistic, and immensely symbolical. There is a predominance of feminine sculpture, for according to Hindu scripture, a temple without the presence of the feminine (and a house without a wife) is without a soul. Women are revered, in principle. There is a plentitude of sculptures in pious and inward contemplative poses, and interspersed generously amongst them are others of a more playful, but symbolic nature; a woman putting on make-up, a woman putting henna designs on her food; a woman pulling a thorn from her foot; a woman, frightened by a monkey, finding refuge in her beloved – much to his obvious delight; couples in loving embrace (sometimes explicitly loving – as one Victorian put it “a little too warm for what is necessary”). But what is so astounding and transporting is the passionless, transcendent splendor of the faces and the purity of love and emotion. I have seen many, many beautiful sculptures with faces of surpassing beauty, ones that turn one’s own soul inward and upward. And these were like those, even transcending them in a different sort of way, in a quiet, pure “goodness”. They were detailed, details of clothing and ornament; indeed, the clothing was sculpted so that it was as if the garments were transparent – how they could make stone seemingly transparent was itself a wonder. And yet, though detailed, it did not transgress into making the faces “realistic”. The simplicity of line combined with the subtlety of design imbued each piece with a transcendent quality, a purity, an impartiality, a soul that has shed it’s own desires and sees only the perfection of the beloved – a gift upon which they look, forever. Finally, it is a work of reverence and piety.

It was said that the sculptor, before beginning work for the day, would begin by bathing, fasting, and praying – often for many hours. Only when his mind was stilled would he enter into the work of art, so that the form that was to be “released” from the stone could come forth. His art: the culmination of generations of artists and a mind and heart free from the needs, fears, and desires of the world.

This place, remote even now, is a journey worth taking. The Chandala empire went into decline in the late 11th century, and these temples lay, half or completely buried in the jungle, for almost 1000 years. They were “rediscovered” in 1838 by an English surveyor but it wasn’t until this century that they were taken under the care of India’s Archeological Survey. Archeological excavations continue; indeed, they are now uncovering a temple which they think will be the largest yet – and there are several more “hills” which probably contain more jewels to be wrested from the arms of the earth that have protected them, these past 900 years.

From one perfection to the next, truly, this country is a wonder of art, of poetry, of genius. We left the wonders of the Mughal world to go backwards again in time. This time, we traveled (uncomfortably) on an amazingly crowded local bus – crowded both inside and on top! Fortunately, we had seats, so by dint of elbow and knee, I could maintain my personal space from encroachment on those who had to stand for the entire 5+ hour journey. It really wasn’t too bad as one’s need for “comfort” lessens with time, which I think is a good thing. I was delighted that our lovely hotel in Khajaraho had a splendid, working, plentiful shower in which I could refresh myself from the experience!

Khajaraho is a city of temples, built at the height of medieval India from 900-1100 AD. It is a city founded both in legend and in history. In legend, it was said that a beautiful maiden was bathing in a lake at night. The moon god, struck by her loveliness, came to earth; the offspring of their love destined to be a great king who would found a kingdom and religious center. In history, it is the seat of the great Chandala kings, kings who, through their might and integrity, maintained their kingdom at this pivotal crossroads against waves of Islamic invasions and who, through their immensity of character and patronage, built these temples of exquisite perfection. Here, we see the culmination and perfection of all that had gone before it. Originally, there were over 85 temples in this area – each a jewel, and each dedicated to some aspect of the divine. Now, 25 temples remain, the most inspiring are 10 set close together. When they were built, these temples surrounded a lake – one can only imagine the splendor of their outlines reflected in the still water.

The glory of these temples is two fold – first of all in the incredible geometry of each temple, an overall geometry, where the spires of a temple increase to the lofty heights of the tall, conical spire that covers the sacred center, a spire reminiscent in design to the lofty mountains of the Himalaya, the abode of the gods. The geometry of the building is then accentuated by the carvings on the outside. From a distance, besides the play of the spires, one against the other, one also notices the interplay of lines, both horizontal and vertical, bands of sculpture that lead the eye around and upward, but predominantly and irresistibly upward toward the liberation of the sky.

Then, as one approaches more closely to the temple, the magnificence of the whole focuses onto the domain of the individual sculptures that surround the temples, row upon row, going both around the temple and upward. Each temple stands on a pedestal. The sculptures, about a foot high on average, on many of the pedestals show everyday life: harvesting, warfare, couples, hunting, a sculptor. The details, even after a thousand years, are astounding. The faces, natural but not naturalistic. Then, as one ascends the steps to the temple proper, one looks at the sculptures surrounding the outside of the temple. Here, the sculptures, often three feet high, are of a more lofty subject, from regal and aristocratic on the bottom tier to the realm of gods as one looks up. Again, the depictions are very detailed, natural but not naturalistic, and immensely symbolical. There is a predominance of feminine sculpture, for according to Hindu scripture, a temple without the presence of the feminine (and a house without a wife) is without a soul. Women are revered, in principle. There is a plentitude of sculptures in pious and inward contemplative poses, and interspersed generously amongst them are others of a more playful, but symbolic nature; a woman putting on make-up, a woman putting henna designs on her food; a woman pulling a thorn from her foot; a woman, frightened by a monkey, finding refuge in her beloved – much to his obvious delight; couples in loving embrace (sometimes explicitly loving – as one Victorian put it “a little too warm for what is necessary”). But what is so astounding and transporting is the passionless, transcendent splendor of the faces and the purity of love and emotion. I have seen many, many beautiful sculptures with faces of surpassing beauty, ones that turn one’s own soul inward and upward. And these were like those, even transcending them in a different sort of way, in a quiet, pure “goodness”. They were detailed, details of clothing and ornament; indeed, the clothing was sculpted so that it was as if the garments were transparent – how they could make stone seemingly transparent was itself a wonder. And yet, though detailed, it did not transgress into making the faces “realistic”. The simplicity of line combined with the subtlety of design imbued each piece with a transcendent quality, a purity, an impartiality, a soul that has shed it’s own desires and sees only the perfection of the beloved – a gift upon which they look, forever. Finally, it is a work of reverence and piety.

It was said that the sculptor, before beginning work for the day, would begin by bathing, fasting, and praying – often for many hours. Only when his mind was stilled would he enter into the work of art, so that the form that was to be “released” from the stone could come forth. His art: the culmination of generations of artists and a mind and heart free from the needs, fears, and desires of the world.

This place, remote even now, is a journey worth taking. The Chandala empire went into decline in the late 11th century, and these temples lay, half or completely buried in the jungle, for almost 1000 years. They were “rediscovered” in 1838 by an English surveyor but it wasn’t until this century that they were taken under the care of India’s Archeological Survey. Archeological excavations continue; indeed, they are now uncovering a temple which they think will be the largest yet – and there are several more “hills” which probably contain more jewels to be wrested from the arms of the earth that have protected them, these past 900 years.

Linda: Taj Mahal – Feb. 8

Taj Mahal – Feb. 8

When one says that one is going to India, the first image that comes to everyone’s mind is the Taj Mahal, one of the Wonders of the World. Indeed, many travel to this amazing country primarily to visit this monument. Being a person who often prefers the less acclaimed sites, I had mixed feelings about coming to Agra. The Taj Mahal is a tomb. It is a tomb in commemoration of a devoted love between the King of much of India, Shah Jahan, and his beloved wife who had died in childbirth, bearing their fourteenth child. Into its design and construction, Shah Jahan poured his soul, his art, and his wealth (much to the chagrin of his son, who, shortly thereafter took over the kingdom from his poet father, locking his father away in the glorious Agra Fort Palace where, until his death, he gazed across the river at the tomb of his beloved).

So much has been said about the glories of the Taj, so many photographs. Though everyone who has been has said it was worth seeing, I wondered. It seems I had seen, through photographs and film, all the moods and angles of this monument.

Words cease. The world stops. Gazing at the Taj, looking from its gates across the lawns and gardens, the pools of water reflecting light, a vision. A pearl drops from heaven and sits just above the earth. It is neither of this world or the next, but seemingly hovers, lightly, iridescently, in graceful perfection. One sits, neither here nor there, transfixed in time, surpassing, surpassing all expectation. Pure contentment and peace is this abode – more than a testament to love, but to Love. A vision to hold onto, to become part of, to turn inward, anywhere and always.

When one says that one is going to India, the first image that comes to everyone’s mind is the Taj Mahal, one of the Wonders of the World. Indeed, many travel to this amazing country primarily to visit this monument. Being a person who often prefers the less acclaimed sites, I had mixed feelings about coming to Agra. The Taj Mahal is a tomb. It is a tomb in commemoration of a devoted love between the King of much of India, Shah Jahan, and his beloved wife who had died in childbirth, bearing their fourteenth child. Into its design and construction, Shah Jahan poured his soul, his art, and his wealth (much to the chagrin of his son, who, shortly thereafter took over the kingdom from his poet father, locking his father away in the glorious Agra Fort Palace where, until his death, he gazed across the river at the tomb of his beloved).

So much has been said about the glories of the Taj, so many photographs. Though everyone who has been has said it was worth seeing, I wondered. It seems I had seen, through photographs and film, all the moods and angles of this monument.

Words cease. The world stops. Gazing at the Taj, looking from its gates across the lawns and gardens, the pools of water reflecting light, a vision. A pearl drops from heaven and sits just above the earth. It is neither of this world or the next, but seemingly hovers, lightly, iridescently, in graceful perfection. One sits, neither here nor there, transfixed in time, surpassing, surpassing all expectation. Pure contentment and peace is this abode – more than a testament to love, but to Love. A vision to hold onto, to become part of, to turn inward, anywhere and always.

Linda: Fatehpur Sikr, Agra, Feb. 7

Linda: Fatehpur Sikr, Agra, Feb. 7

We arrived in the ancient Mughal capital of Agra late at night to a little hotel, yards from the Taj Mahal and surrounded by lovely gardens. The next morning, we left on a local bus to the abandoned city of Fatehpur Sikr. This city was built by the great King Akbar in the late 1500’s.

Sometimes, one has the privilege of seeing into the soul of a great man. This city was such a glimpse - this city, set on top of a ridge overlooking the surrounding fields and forests. Of all the stories of kings throughout the world, the story of Akbar has been, for me, one of the most inspiring (Ashoka and Charlemagne also come to mind. Yes, I love the legends of King Arthur and there are kings and queens throughout all the regions of the world that one admires – for reasons similar to Akbar. But unlike Arthur, or Rama, or Krishna whose “reality” is steeped in legend and symbolism and other of great kings of the misty past, Akbar was recent and one can get a sense of him through the history, poetry, prose, architecture, and art inspired by his reign and his patronage.

Akbar was born into royalty. He was of the Islamic faith and his forefathers were carving kingdoms into the northern areas of India, off and on, for the previous few centuries. Akbar was, like all kings of his time, a warrior king, but of the greatest kind, for he was not inspired by conquest, personal glory, and gain, but had a higher aim. He was a man of great vision, compassion, strength of character, piety, humility, and had an understanding of humanity that is a light for all times. (Perhaps the ancient kings whose greatness of heart inspired the temples in southern India were other men of this sort.) Though illiterate, he surrounded himself by the great minds of the age, in all fields, in all religions. He kept, on hand, over 50,000 manuscripts which traveled with him from capital to capital, palace to palace. He would be read to, for hours daily, and memorized vast amounts of information and pearls of wisdom. He sought advice, discerning truth and wisdom. He conquered many lands, but with a wisdom and compassion that brought peace and light to the realms that surrounded him. Such was his realm that all who were knowledgeable were welcome. He abolished taxes and fines that were given to those of a different religion. He employed Hindus, Christians, Parsis, Muslims, and Jews in high positions in court, much like the early Ottomans in Turkey and the Andalusian rulers in Spain. He had several wives, in keeping with eastern tradition and royal necessity, some of whom were of different religions and all of whom were treated with reverence and respect. They, too, wielded an influence in their own right. His was a realm where character, intelligence, and integrity mattered most – and it was in a relatively recent day and age.

Fatehhpur Sikri was the dream of this great man. His capital was at Agra Fort, where, surrounded by his court, he ruled … childless. He sought the blessing of a great Sufi teacher, and, after consulting and being guided by this Sufi teacher, his wife conceived a son and heir. In gratitude, he conceived of a plan for a city, starting with a mosque and surrounding grounds that would house scholars and poets and leaders of the Islamic faith. The grounds would also become the site of the tomb of the Sufi saint, Mu’in ad-Din Chishti. This was the first place we visited in Fatehpur Sikr, a place still living despite its remoteness, where pilgrims come to the tomb and tie a string on the stone screens that surround it – a heartfelt prayer, a hope for the future.

Then, over a course of 16 years, the rest of this magnificent palace was built. Inside its grounds, the palaces of the queens lay in stately array and the private quarters of the great king were a testament to his vision. This palace, built as a refuge from the court of Agra, was like a legend come to life. All was light and airy, with wide courtyards, fountains, blue sky, and wind. It was designed to catch all the winds, keeping the grounds and various buildings cool. It was made for the people to always be accessible to their king, with a large and impressive Hall for Public Audiences (for any citizen of the realm) as well as a smaller, more private and intimate (but equally impressive) Hall for Private Audiences. This hall in particular was a window into his soul, for it was not only designed as an audience chamber for higher ranking officials and aristocrats, but was also a great chamber for debate. In the center of the hall, open on all sides, is a large column, connected by light and fanciful bridges to the four upper corners of the building. Akbar would stand in the center, on top of the column, and have representatives of different points of view – often of the different religions of his realm – in each corner. From there, debate would ensue – king debating in an open and respectful fashion with the great minds of his time. All would be pursuing that highest common thread, that transcendent unity that binds all, and upon which he built his kingdom. His power, both military and financial, allowed this, despite grumblings amongst those with a less lofty vision. And, for his lifetime and the lifetime of his son, such were the times where all were valued for their humanity, their piety, their wisdom, their character, their art, and their strength of will.

Each building is a jewel. The Treasury – amazingly open, though one sees the remnants of where huge doors closed off various parts. The palaces of the queens, whose walls are decorated with that wonderful Islamic art that turns stone into something of air and light, twining arabesques that bring both privacy and light. The library, the fountain with a large platform in the center where one can sit, surrounded by light and water. There was even a court sized (LARGE) Pachisi board, played with women as the playing pieces – 16 games played before all was done! An abode of peace. A haven of beauty. A place of prayer. A paradise on earth.

But, like all things in this world, it passed. And as things are of this later age, its time was quick, a swan song in the night. Though highly engineered, water became a significant issue in this great palace, and after a mere 14 years, the gates were locked and the palaces were closed, abandoned, and preserved in their entirety, a dream frozen in time.

After the wonder of the Hindu architecture with which we have been immersed, dropping into this splendid city of Islamic grandeur, with its sweeping views, its light and airy magnificence, it’s emphasis on truth and compassion and humanity and art, was a journey into another world – one in which one can see all that is good and beautiful about the peoples of this religion, brought to light through the soul and patronage of a great man.

We arrived in the ancient Mughal capital of Agra late at night to a little hotel, yards from the Taj Mahal and surrounded by lovely gardens. The next morning, we left on a local bus to the abandoned city of Fatehpur Sikr. This city was built by the great King Akbar in the late 1500’s.

Sometimes, one has the privilege of seeing into the soul of a great man. This city was such a glimpse - this city, set on top of a ridge overlooking the surrounding fields and forests. Of all the stories of kings throughout the world, the story of Akbar has been, for me, one of the most inspiring (Ashoka and Charlemagne also come to mind. Yes, I love the legends of King Arthur and there are kings and queens throughout all the regions of the world that one admires – for reasons similar to Akbar. But unlike Arthur, or Rama, or Krishna whose “reality” is steeped in legend and symbolism and other of great kings of the misty past, Akbar was recent and one can get a sense of him through the history, poetry, prose, architecture, and art inspired by his reign and his patronage.

Akbar was born into royalty. He was of the Islamic faith and his forefathers were carving kingdoms into the northern areas of India, off and on, for the previous few centuries. Akbar was, like all kings of his time, a warrior king, but of the greatest kind, for he was not inspired by conquest, personal glory, and gain, but had a higher aim. He was a man of great vision, compassion, strength of character, piety, humility, and had an understanding of humanity that is a light for all times. (Perhaps the ancient kings whose greatness of heart inspired the temples in southern India were other men of this sort.) Though illiterate, he surrounded himself by the great minds of the age, in all fields, in all religions. He kept, on hand, over 50,000 manuscripts which traveled with him from capital to capital, palace to palace. He would be read to, for hours daily, and memorized vast amounts of information and pearls of wisdom. He sought advice, discerning truth and wisdom. He conquered many lands, but with a wisdom and compassion that brought peace and light to the realms that surrounded him. Such was his realm that all who were knowledgeable were welcome. He abolished taxes and fines that were given to those of a different religion. He employed Hindus, Christians, Parsis, Muslims, and Jews in high positions in court, much like the early Ottomans in Turkey and the Andalusian rulers in Spain. He had several wives, in keeping with eastern tradition and royal necessity, some of whom were of different religions and all of whom were treated with reverence and respect. They, too, wielded an influence in their own right. His was a realm where character, intelligence, and integrity mattered most – and it was in a relatively recent day and age.

Fatehhpur Sikri was the dream of this great man. His capital was at Agra Fort, where, surrounded by his court, he ruled … childless. He sought the blessing of a great Sufi teacher, and, after consulting and being guided by this Sufi teacher, his wife conceived a son and heir. In gratitude, he conceived of a plan for a city, starting with a mosque and surrounding grounds that would house scholars and poets and leaders of the Islamic faith. The grounds would also become the site of the tomb of the Sufi saint, Mu’in ad-Din Chishti. This was the first place we visited in Fatehpur Sikr, a place still living despite its remoteness, where pilgrims come to the tomb and tie a string on the stone screens that surround it – a heartfelt prayer, a hope for the future.

Then, over a course of 16 years, the rest of this magnificent palace was built. Inside its grounds, the palaces of the queens lay in stately array and the private quarters of the great king were a testament to his vision. This palace, built as a refuge from the court of Agra, was like a legend come to life. All was light and airy, with wide courtyards, fountains, blue sky, and wind. It was designed to catch all the winds, keeping the grounds and various buildings cool. It was made for the people to always be accessible to their king, with a large and impressive Hall for Public Audiences (for any citizen of the realm) as well as a smaller, more private and intimate (but equally impressive) Hall for Private Audiences. This hall in particular was a window into his soul, for it was not only designed as an audience chamber for higher ranking officials and aristocrats, but was also a great chamber for debate. In the center of the hall, open on all sides, is a large column, connected by light and fanciful bridges to the four upper corners of the building. Akbar would stand in the center, on top of the column, and have representatives of different points of view – often of the different religions of his realm – in each corner. From there, debate would ensue – king debating in an open and respectful fashion with the great minds of his time. All would be pursuing that highest common thread, that transcendent unity that binds all, and upon which he built his kingdom. His power, both military and financial, allowed this, despite grumblings amongst those with a less lofty vision. And, for his lifetime and the lifetime of his son, such were the times where all were valued for their humanity, their piety, their wisdom, their character, their art, and their strength of will.

Each building is a jewel. The Treasury – amazingly open, though one sees the remnants of where huge doors closed off various parts. The palaces of the queens, whose walls are decorated with that wonderful Islamic art that turns stone into something of air and light, twining arabesques that bring both privacy and light. The library, the fountain with a large platform in the center where one can sit, surrounded by light and water. There was even a court sized (LARGE) Pachisi board, played with women as the playing pieces – 16 games played before all was done! An abode of peace. A haven of beauty. A place of prayer. A paradise on earth.

But, like all things in this world, it passed. And as things are of this later age, its time was quick, a swan song in the night. Though highly engineered, water became a significant issue in this great palace, and after a mere 14 years, the gates were locked and the palaces were closed, abandoned, and preserved in their entirety, a dream frozen in time.

After the wonder of the Hindu architecture with which we have been immersed, dropping into this splendid city of Islamic grandeur, with its sweeping views, its light and airy magnificence, it’s emphasis on truth and compassion and humanity and art, was a journey into another world – one in which one can see all that is good and beautiful about the peoples of this religion, brought to light through the soul and patronage of a great man.

Sunday, February 8, 2009

Linda: Bodhgaya, Feb. 2-6

Linda: Bodhgaya – Feb 1-5

With much trepidation and a heavy heart, I said farewell to my husband and son on the streets of Varanasi. It has been a wonderful 6 weeks, a treasured time with many diverse events and a blessing to share as a family.

Eleanor and I left for the train station long before Patrick and Matthew. It was our first time on Indian trains – 3 hours late, three tier sleeper car. We only had a 5 hour journey, but my, those seats got hard by the end of the five hours! The trains are certainly less bumpy than travel by bus and one can lie down. We were in a second class compartment and it was cold enough that my shawl was very welcomed. Our compartment was shared with an Indian couple, a man from Austria, and a man from Japan. Both of these men had been to India before and were returning to re-visit some places and explore new areas. (December/January really is the best time to see most of India as the weather is, on the whole, quite pleasant.) The train is an excellent place to meet people, to compare notes, to play cards, to show photographs, and to share food – if one dares. Passengers come well supplied with many savory items and meals. The train stops about every 15 minutes, so a five hour trip by train would probably take half as long by car. At most stops, people would come on board offering tea and snacks, and often someone would come on board to beg for money. One ingenious little girl came on and did acrobatics in the hopes of making a few rupees. It worked on Eleanor! (In Varanasi, we have seen the most extreme cases of poverty and crippled people trying to survive. Because of the expense of medicine, many injuries go untreated, so it is not uncommon to see someone with twisted limbs. Some walk or creep along the ground, making their way the best they can. How incredibly difficult life can be.)

We are on our way to Bodhgaya, the place where the Buddha sat under a banyan tree and attained Enlightenment. It is the most significant place of pilgrimage for the Buddhist world, and the tree, stupa, and surrounding grounds are a World Heritage Site. We arrived at 1:00 in the morning to a sleeping town and slept later that morning and had brunch. We just went around the corner, past a few shops selling things and one beautiful Tibetan monastery that is across the street from our hotel. After eating an exquisite meal in a little Tibetan café, we made our way to the grounds where the Buddha had meditated 2500 years ago. And there, we had an immense surprise. As we neared the ground, we heard chanting and horns coming from within the gates. The stupa is a beautiful structure, and the grounds are surrounded by flowers, gardens, votive pillars, little buildings. At Sarnath, I had fervently wished to see a place that was living, vibrant, still manifesting what had inspired its creation. I wanted to see what Sarnath once was – and here it was! All the sacred architecture I’d wondered about in the ruins of Sarnath were here. And more! We came during the three days when relics, sacred to the Tibetan Buddhists, were on display. We came in the center of a large Tibetan pilgrimage. The grounds around the Bodhgaya tree were surrounded by thousands of Tibetan monks and nuns with their beautiful countenances and robes of maroon and ochre. Other nationalities were also present, all sitting around the stupa, praying, prostrating, chanting, reading. There are two walkways around the stupa; the first one is about 15 steps above ground level and the second another 15 steps above that. One could walk on the upper level, going around the stupa, and looking down at this immense spectacle. Because the walkway was up, I felt completely at ease taking photographs, knowing I did not distract the people praying below. It is a very serene and peaceful place here. It’s a quiet place, an inward place.

Going on at the same time is the Saraswati celebration, a Hindu celebration of a significant goddess. During this time, statues of Saraswati are taken out of the temples to be led in procession down the streets. In Varanasi, she is taken to the Ganges to be plunged in her waters before returning to the temples. I’m not sure where they took her here in Bodhgaya. It was such an interesting contrast between the two modes! The Buddhist monks and nuns were all around the tree, chanting and praying. Then, occasionally, out in the streets, one would hear loud drumming and playing (sometimes loudspeakers playing Hindu music). If you were out on the street, you would see a truck coming, decked in flowers with musicians in front. The statue of Saraswati would be on the bed of the truck, resplendent with flowers and fabric, followed by devotees dancing (all men, at least I don’t think I saw any women) and singing in the streets. This scene would be played off and on over a three day period – a little wild and very festive.

The Bodhgaya is a wonderful place, and the surrounding monasteries are also a wonder. Every Buddhist country was invited to build a monastery in the style of their country. So, even though there were mainly Tibetans here at this time, one also saw significant numbers of Chinese, Bhutanese, Burmese, Vietnamese, Japanese, Thai, Indian and others. Some of the temples are absolute jewels, and in seeing the various temples, one sees a significant part of the Asian world. Truly, I marvel at the artistry that takes the same ideas, the same sets of principles, the same stories, and transforms them into archtypes that beautifully reflect a people’s hearts. The Tibetan monastary with its bright colors; the Bhutanese with more subdued colors and three-dimensional scenes in the walls; the Japanese with its stark and simple building whose austerity offset the resplendent Buddha that was at its center; the Thai temple with its exquisite blue and gold and the Buddha with the Thai style crown that connects man with heaven. In Thailand, people always sense the connection between man and God as a direct link between the head and heaven. Their artwork and halos reflect this, and it is considered very bad manners to touch someone on the head, as this cuts this connection. The artwork reminded me in some ways of the Christian art work of the descent of the Holy Spirit. One walks here, somewhere in a different time and in a different place. How small our world is, how wonderful, and how fragile.

(I am now back to being a minority again! And so are all the Hindus!)

For three days, we basked in the contemplative splendor of the Tibetan prayer life. I was quite tired from all the traveling and did not take as full advantage of this situation as possible. Besides the large gatherings at the site of the Bodhi Tree, there were also smaller, more intimate gatherings at the various monasteries, both early in the morning and later in the afternoon. The atmosphere vibrated with the hum of prayerful intent, and one’s heart was swept up with a calmness, a sense that it would be so easy to live this quiet, unhurried pace, letting the moments go by in a simple life of a plain diet, a simple room, and the pursuit of knowledge and understanding in the highest form.

Today is our last day here. I awoke after a fitful night, feeling quite restless and out of sorts – a significant contrast to the previous days of contentment. When Eleanor and I left to go to the Bodhi Tree, we saw that, indeed, all was over. The little blankets that had covered the walkways, resplendent with beads, prayer wheels, flags, and jewelry from Tibet were mostly gone and, inside the courtyards of the stupa, a few monks continued to pray and prostrate, but all else was being cleaned up. The bowls of flowers that had surrounded all the walkways were gone. The thousands of oil lamps, flickering on the walkways and in the 5 glass houses that contained them were all extinguished. Buses were lining up, dignitaries were leaving, and many of the Tibetans had taken off their beautiful robes for the western dress in which they would travel. One could see monks and nuns, lingering on the periphery, trying to hold onto the peace that had been there, something to savor and hold onto – perhaps for a lifetime. Others were already thinking of tomorrow, their faces already turned away. Transitions are such difficult times, and I found it interesting that the very air around us transmitted this; we were surrounded by an unsettled ambience saying it was time to move on. Still, to have been given this fleeting glance into this world, so unexpected, was a true gift – one of those moments forever in one’s imagination, like photographs which can be viewed, reminders of a happiness and a fleeting perfection in an imperfect world.

With much trepidation and a heavy heart, I said farewell to my husband and son on the streets of Varanasi. It has been a wonderful 6 weeks, a treasured time with many diverse events and a blessing to share as a family.

Eleanor and I left for the train station long before Patrick and Matthew. It was our first time on Indian trains – 3 hours late, three tier sleeper car. We only had a 5 hour journey, but my, those seats got hard by the end of the five hours! The trains are certainly less bumpy than travel by bus and one can lie down. We were in a second class compartment and it was cold enough that my shawl was very welcomed. Our compartment was shared with an Indian couple, a man from Austria, and a man from Japan. Both of these men had been to India before and were returning to re-visit some places and explore new areas. (December/January really is the best time to see most of India as the weather is, on the whole, quite pleasant.) The train is an excellent place to meet people, to compare notes, to play cards, to show photographs, and to share food – if one dares. Passengers come well supplied with many savory items and meals. The train stops about every 15 minutes, so a five hour trip by train would probably take half as long by car. At most stops, people would come on board offering tea and snacks, and often someone would come on board to beg for money. One ingenious little girl came on and did acrobatics in the hopes of making a few rupees. It worked on Eleanor! (In Varanasi, we have seen the most extreme cases of poverty and crippled people trying to survive. Because of the expense of medicine, many injuries go untreated, so it is not uncommon to see someone with twisted limbs. Some walk or creep along the ground, making their way the best they can. How incredibly difficult life can be.)

We are on our way to Bodhgaya, the place where the Buddha sat under a banyan tree and attained Enlightenment. It is the most significant place of pilgrimage for the Buddhist world, and the tree, stupa, and surrounding grounds are a World Heritage Site. We arrived at 1:00 in the morning to a sleeping town and slept later that morning and had brunch. We just went around the corner, past a few shops selling things and one beautiful Tibetan monastery that is across the street from our hotel. After eating an exquisite meal in a little Tibetan café, we made our way to the grounds where the Buddha had meditated 2500 years ago. And there, we had an immense surprise. As we neared the ground, we heard chanting and horns coming from within the gates. The stupa is a beautiful structure, and the grounds are surrounded by flowers, gardens, votive pillars, little buildings. At Sarnath, I had fervently wished to see a place that was living, vibrant, still manifesting what had inspired its creation. I wanted to see what Sarnath once was – and here it was! All the sacred architecture I’d wondered about in the ruins of Sarnath were here. And more! We came during the three days when relics, sacred to the Tibetan Buddhists, were on display. We came in the center of a large Tibetan pilgrimage. The grounds around the Bodhgaya tree were surrounded by thousands of Tibetan monks and nuns with their beautiful countenances and robes of maroon and ochre. Other nationalities were also present, all sitting around the stupa, praying, prostrating, chanting, reading. There are two walkways around the stupa; the first one is about 15 steps above ground level and the second another 15 steps above that. One could walk on the upper level, going around the stupa, and looking down at this immense spectacle. Because the walkway was up, I felt completely at ease taking photographs, knowing I did not distract the people praying below. It is a very serene and peaceful place here. It’s a quiet place, an inward place.

Going on at the same time is the Saraswati celebration, a Hindu celebration of a significant goddess. During this time, statues of Saraswati are taken out of the temples to be led in procession down the streets. In Varanasi, she is taken to the Ganges to be plunged in her waters before returning to the temples. I’m not sure where they took her here in Bodhgaya. It was such an interesting contrast between the two modes! The Buddhist monks and nuns were all around the tree, chanting and praying. Then, occasionally, out in the streets, one would hear loud drumming and playing (sometimes loudspeakers playing Hindu music). If you were out on the street, you would see a truck coming, decked in flowers with musicians in front. The statue of Saraswati would be on the bed of the truck, resplendent with flowers and fabric, followed by devotees dancing (all men, at least I don’t think I saw any women) and singing in the streets. This scene would be played off and on over a three day period – a little wild and very festive.

The Bodhgaya is a wonderful place, and the surrounding monasteries are also a wonder. Every Buddhist country was invited to build a monastery in the style of their country. So, even though there were mainly Tibetans here at this time, one also saw significant numbers of Chinese, Bhutanese, Burmese, Vietnamese, Japanese, Thai, Indian and others. Some of the temples are absolute jewels, and in seeing the various temples, one sees a significant part of the Asian world. Truly, I marvel at the artistry that takes the same ideas, the same sets of principles, the same stories, and transforms them into archtypes that beautifully reflect a people’s hearts. The Tibetan monastary with its bright colors; the Bhutanese with more subdued colors and three-dimensional scenes in the walls; the Japanese with its stark and simple building whose austerity offset the resplendent Buddha that was at its center; the Thai temple with its exquisite blue and gold and the Buddha with the Thai style crown that connects man with heaven. In Thailand, people always sense the connection between man and God as a direct link between the head and heaven. Their artwork and halos reflect this, and it is considered very bad manners to touch someone on the head, as this cuts this connection. The artwork reminded me in some ways of the Christian art work of the descent of the Holy Spirit. One walks here, somewhere in a different time and in a different place. How small our world is, how wonderful, and how fragile.

(I am now back to being a minority again! And so are all the Hindus!)

For three days, we basked in the contemplative splendor of the Tibetan prayer life. I was quite tired from all the traveling and did not take as full advantage of this situation as possible. Besides the large gatherings at the site of the Bodhi Tree, there were also smaller, more intimate gatherings at the various monasteries, both early in the morning and later in the afternoon. The atmosphere vibrated with the hum of prayerful intent, and one’s heart was swept up with a calmness, a sense that it would be so easy to live this quiet, unhurried pace, letting the moments go by in a simple life of a plain diet, a simple room, and the pursuit of knowledge and understanding in the highest form.

Today is our last day here. I awoke after a fitful night, feeling quite restless and out of sorts – a significant contrast to the previous days of contentment. When Eleanor and I left to go to the Bodhi Tree, we saw that, indeed, all was over. The little blankets that had covered the walkways, resplendent with beads, prayer wheels, flags, and jewelry from Tibet were mostly gone and, inside the courtyards of the stupa, a few monks continued to pray and prostrate, but all else was being cleaned up. The bowls of flowers that had surrounded all the walkways were gone. The thousands of oil lamps, flickering on the walkways and in the 5 glass houses that contained them were all extinguished. Buses were lining up, dignitaries were leaving, and many of the Tibetans had taken off their beautiful robes for the western dress in which they would travel. One could see monks and nuns, lingering on the periphery, trying to hold onto the peace that had been there, something to savor and hold onto – perhaps for a lifetime. Others were already thinking of tomorrow, their faces already turned away. Transitions are such difficult times, and I found it interesting that the very air around us transmitted this; we were surrounded by an unsettled ambience saying it was time to move on. Still, to have been given this fleeting glance into this world, so unexpected, was a true gift – one of those moments forever in one’s imagination, like photographs which can be viewed, reminders of a happiness and a fleeting perfection in an imperfect world.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)