Khajaraho, Feb. 9-12

From one perfection to the next, truly, this country is a wonder of art, of poetry, of genius. We left the wonders of the Mughal world to go backwards again in time. This time, we traveled (uncomfortably) on an amazingly crowded local bus – crowded both inside and on top! Fortunately, we had seats, so by dint of elbow and knee, I could maintain my personal space from encroachment on those who had to stand for the entire 5+ hour journey. It really wasn’t too bad as one’s need for “comfort” lessens with time, which I think is a good thing. I was delighted that our lovely hotel in Khajaraho had a splendid, working, plentiful shower in which I could refresh myself from the experience!

Khajaraho is a city of temples, built at the height of medieval India from 900-1100 AD. It is a city founded both in legend and in history. In legend, it was said that a beautiful maiden was bathing in a lake at night. The moon god, struck by her loveliness, came to earth; the offspring of their love destined to be a great king who would found a kingdom and religious center. In history, it is the seat of the great Chandala kings, kings who, through their might and integrity, maintained their kingdom at this pivotal crossroads against waves of Islamic invasions and who, through their immensity of character and patronage, built these temples of exquisite perfection. Here, we see the culmination and perfection of all that had gone before it. Originally, there were over 85 temples in this area – each a jewel, and each dedicated to some aspect of the divine. Now, 25 temples remain, the most inspiring are 10 set close together. When they were built, these temples surrounded a lake – one can only imagine the splendor of their outlines reflected in the still water.

The glory of these temples is two fold – first of all in the incredible geometry of each temple, an overall geometry, where the spires of a temple increase to the lofty heights of the tall, conical spire that covers the sacred center, a spire reminiscent in design to the lofty mountains of the Himalaya, the abode of the gods. The geometry of the building is then accentuated by the carvings on the outside. From a distance, besides the play of the spires, one against the other, one also notices the interplay of lines, both horizontal and vertical, bands of sculpture that lead the eye around and upward, but predominantly and irresistibly upward toward the liberation of the sky.

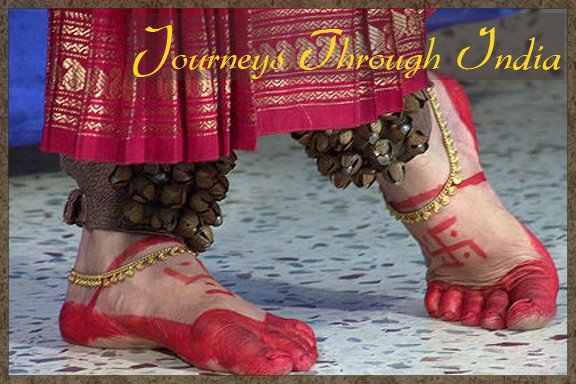

Then, as one approaches more closely to the temple, the magnificence of the whole focuses onto the domain of the individual sculptures that surround the temples, row upon row, going both around the temple and upward. Each temple stands on a pedestal. The sculptures, about a foot high on average, on many of the pedestals show everyday life: harvesting, warfare, couples, hunting, a sculptor. The details, even after a thousand years, are astounding. The faces, natural but not naturalistic. Then, as one ascends the steps to the temple proper, one looks at the sculptures surrounding the outside of the temple. Here, the sculptures, often three feet high, are of a more lofty subject, from regal and aristocratic on the bottom tier to the realm of gods as one looks up. Again, the depictions are very detailed, natural but not naturalistic, and immensely symbolical. There is a predominance of feminine sculpture, for according to Hindu scripture, a temple without the presence of the feminine (and a house without a wife) is without a soul. Women are revered, in principle. There is a plentitude of sculptures in pious and inward contemplative poses, and interspersed generously amongst them are others of a more playful, but symbolic nature; a woman putting on make-up, a woman putting henna designs on her food; a woman pulling a thorn from her foot; a woman, frightened by a monkey, finding refuge in her beloved – much to his obvious delight; couples in loving embrace (sometimes explicitly loving – as one Victorian put it “a little too warm for what is necessary”). But what is so astounding and transporting is the passionless, transcendent splendor of the faces and the purity of love and emotion. I have seen many, many beautiful sculptures with faces of surpassing beauty, ones that turn one’s own soul inward and upward. And these were like those, even transcending them in a different sort of way, in a quiet, pure “goodness”. They were detailed, details of clothing and ornament; indeed, the clothing was sculpted so that it was as if the garments were transparent – how they could make stone seemingly transparent was itself a wonder. And yet, though detailed, it did not transgress into making the faces “realistic”. The simplicity of line combined with the subtlety of design imbued each piece with a transcendent quality, a purity, an impartiality, a soul that has shed it’s own desires and sees only the perfection of the beloved – a gift upon which they look, forever. Finally, it is a work of reverence and piety.

It was said that the sculptor, before beginning work for the day, would begin by bathing, fasting, and praying – often for many hours. Only when his mind was stilled would he enter into the work of art, so that the form that was to be “released” from the stone could come forth. His art: the culmination of generations of artists and a mind and heart free from the needs, fears, and desires of the world.

This place, remote even now, is a journey worth taking. The Chandala empire went into decline in the late 11th century, and these temples lay, half or completely buried in the jungle, for almost 1000 years. They were “rediscovered” in 1838 by an English surveyor but it wasn’t until this century that they were taken under the care of India’s Archeological Survey. Archeological excavations continue; indeed, they are now uncovering a temple which they think will be the largest yet – and there are several more “hills” which probably contain more jewels to be wrested from the arms of the earth that have protected them, these past 900 years.

Wednesday, February 11, 2009

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment