Norbulingka Institute

Preserving Tibetan Culture

(Significant portions of this text are due to the literature available at Norbulingka)

I keep thinking that nothing more will happen, and yet, other jewels keep being added to this crown of wonder. Today, I splurged and hired a taxi for the day ($18 for the day) and went to the other side of Dharamsala to see the Norbulingka Institute for Tibetan Arts. I set aside 2 hours to visit the Institute and would then go to Gyuko Monastery for a teaching a blessing by His Holiness the Karmapa.

The Norbulingka Institute was tucked away, up small windy (bumpy) roads. They operate workshops in which the sacred and traditional arts of Tibet are passed down to a new generation by masters who were trained in Tibet. Many of these skills and traditions are dying out in the exile community. In Tibet itself, art and culture are regarded as expressions of Tibetan identity and receive scant encouragement.

One arrives in front a building built in a traditional Tibetan style with exposed and brightly painted wooden beams. You walk through a breezeway and enter another world. Most of this part of the compound is a spectacular Japanese garden with meandering stone paths and walls, cascading waterfalls, and flower filled pools and ponds. It is serene, shady, and beautifully quiet. To the right is a café, with tables overlooking the gardens and pools. To the left is a beautiful guest house, rooms starting at $20 a night.

One meanders through the gardens before arriving at a tall sweep of steps surrounded by ponds and a group of Tibetan buildings. The stairs lead to a hallway or gateway lined with prayer wheels that opens into a courtyard, more cascading water, and a stunning array of Tibetan buildings. The centerpiece of the complex is a temple situated at the top of the hill. It is the highest point, the most important point, and a constant reminder of why one is here. The temple itself is exquisite. All the work in the temple was done by the master artists of Norbulingka. The murals are extraordinary. The details exquisite. The effect, calming, uplifting, interiorizing. A Tibetan man sits near a column, spinning a large prayer wheel. Another is nearby saying prayers on a rosary. A woman in the corner is reciting from a sacred text. Other Tibetans come and go, prostrating before the golden Buddha that fills the center of the back wall. Though this is an institute for the arts, it is also a community. I have never seen the sacred and the traditional recreated in this way. (This Institute was started in 1995.) Usually it is one or the other. Here, it is both, integrated.

This is, primarily, a school for traditional Tibetan arts. Within the buildings, artisans are painting and doing appliqué Thangkas, carving wood, and creating bronze statues, using only traditional models and traditional materials as tools and as supplies. The most stunning displays were the traditional painting of Buddhist deities, Thangkas. Thangkas are not simply a decoration or beautiful creation, but a religious object and a medium for expressing Buddhist ideals. They are used by Buddhists as an aid to clear visualization of an image of a deity, with a view to developing a close relationship with that deity. In the old days, Thangkas often were a result of the visions or dreams of great lamas or meditators who also possessed artistic talent. They condensed the whole of their realization into a particular image. Such an image will also access to the lama’s deep realization and help the practitioner on the spiritual path. In town, I have been looking at the thangkas for the past several days, admiring their art and their symbolism. Here at Norbulingka, only natural paints are used, paints derived from plants, from crushed precious and semi-precious stones, and from metal, especially gold. The difference is profound. The colors are rich and deep without the shininess and harshness that artificial colors can have. The colors themselves have a presence, and their intense beauty adds much to the quality of the thangkas and the presence of the deities. A painter begins by stretching his canvas over a wooden frame with cords. The cloth is then sealed with a moist mixture of chalk and gesso and the surface is polished with a smooth stone or glass until the underlying texture of the canvas is no longer present. The design for the painting is drawn directly onto the canvas using a grid which allows a proportionally correct image, irrespective of the size of the canvas. Next, color is applied. Mostly crushed minerals are used, and vegetable matter is mixed with gesso. Finally the details of the faces are added (Last – I thought that was interesting and symbolic. The deity needs their surrounding before they can be present in the painting.) and gold is applied. Traditionally, thangkas are then framed in silk brocade. Students study painting for three years before mastering the skills and techniques required. A painting is done by one artist, from beginning to end. A single painting will take three to seven months to complete.

Another traditional art form, related to thangka painting is thangka appliqué made entirely from silk and brocade. The silk and brocade add texture and vibrancy to the images. This art form goes back many centuries, and thangka appliqué was established in the highest ranks of the tailoring guild in Tibet. They worked with the thangka painters to set the proportions and outlines of the deities. Tailors usually joined the guild very young and spent months practicing sewing by hand until they reached remarkable standards of evenness and speed. The appliqué artists begin by preparing the stencil of the central figure. Using this stencil, hundreds of pieces are hand cut (tiny scissors!) from colored silk and brocade. The image of the deity is then assembled from the individual pieces, each of which is outlined with silk-wrapped strands of hair from a horse’s tail. The complete piece is then attached to the background and other smaller figures and landscape details are added using the same method to form a complete thangka. Finally, the finished appliqué image is set in a brocade border. Applique thangkas are a group effort, with different artisans doing different parts of the process. Artisans will study this art form for two to three years before mastering the various processes. An appliqué thangka will take four to seven months to complete.

Statue making requires a twelve year apprenticeship. Two major sculptural traditions flourished in Tibet, one that modeled statues of clay and another that made statues of metal. The metal statues are made using two different processes. The lost wax process is used for casting small statues, while large statues are hammered from sheets of copper. To create the life-size and colossal statues from sheets of copper involves two highly skilled techniques, repousse′, in which the copper is worked using a hammer and shaping tools from the reverse side, and chasing. These techniques allow the achievement of tremendous detail, not only with regard to facial and other features, but also in the remarkable flow of garments and the rich decoration of ornamental haloes. The drawing of the deity is first made on paper and then transferred to the copper sheet. Intricate pieces are shaped, suing repousse′ and chasing while the copper sheet is supported on a bed of natural resin. Occasional heating of the copper improves its malleability. Every detail, such as ornaments and the halo of a statue is precisely designed and prepared by the master. The larger parts of a statue are made using the same technique, with each piece hand beaten and shaped from copper sheets. Smaller parts of the sculptures are cast using the sand-casting process. Once the large parts of the statue have been shaped, the detailed ornaments and accessories are added and the statue is assembled. Gilding the statue and painting the features of the face on the statue can further enhance their positive potential. Gold adds value and represents purity while painting the feature is akin to giving the statue life. Many statues have an ornate crown inlayed with precious stones.

Wood carving of lovely tables, stands, and chairs is also done, first on soft wood and then on teak. The details are beautiful and remind me of the lacelike stone screens of Jaisalmar. Their filigree like detail takes away the heaviness of the wood and the painting adds the vibrancy and color so important in the high mountain regions of Tibet.

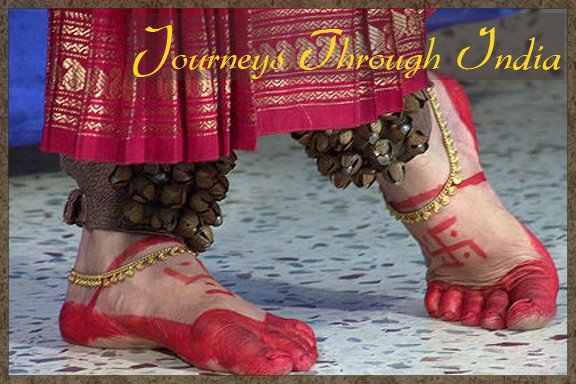

And if wandering around the gardens, temple, art studios, shop, and art museum were not enough, there is also an exquisite doll museum!! Inside are hundreds of stunning dolls of Tibetan people in their various tribal and ceremonial dress. The added bonus is that the dolls are set in dioramas, so that the dolls of monks in their red robes are set in front of a painting of the monastery of Lhasa. Other dolls are displayed in yurts and picnic tents, a king’s palace, or on a river. The attire, the faces, the scenes, the jewelry – all are glimpses into a world that has almost vanished.

As I type these words, a candlelight procession of monks, nuns, and Tibetans winds its way down the street, praying for the preservation of the Tibetan way of life and a return to their homeland – touching in its simplicity and its advocacy of a non-violent solution to the devastation in Tibet.

Monday, April 27, 2009

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment